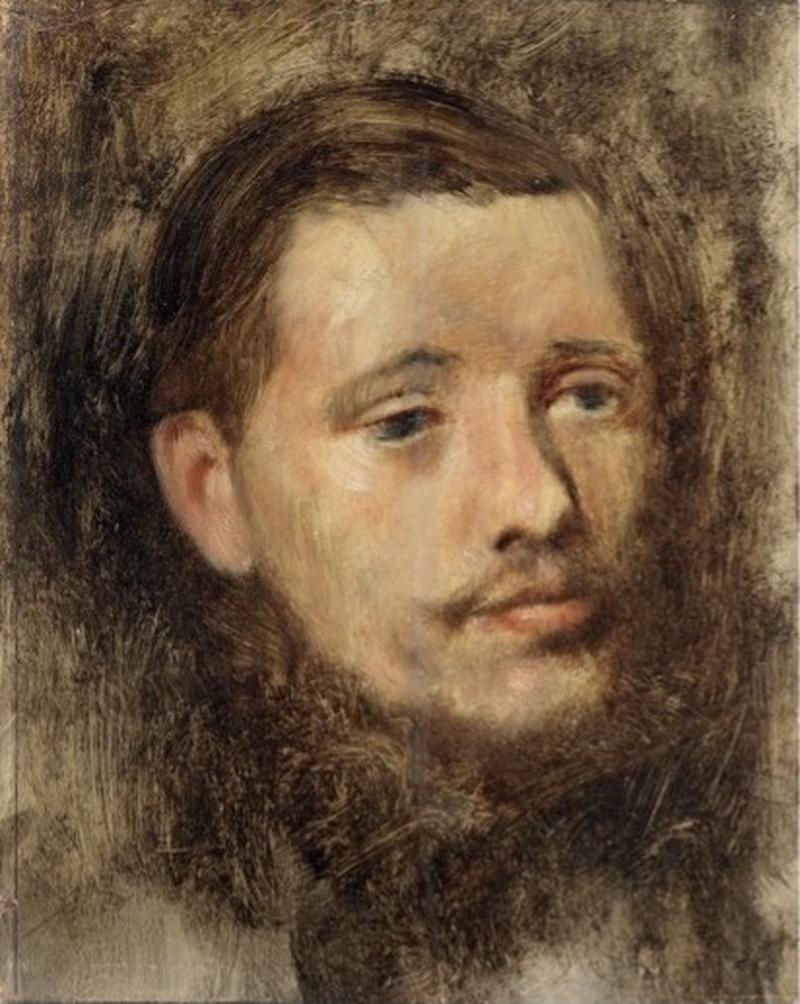

Portrait D'Achille Degas

‘Make portraits of people in typical, familiar poses’ (An excerpt from Degas' notebooks in the late 1860s, quoted in Exh. cat., Degas Portraits, Zurich, 1994, p. 90).

Dating from circa 1864, the present work was painted just a few years before Degas turned towards the ballet as his primary inspiration; however, the portraits of his early oeuvre are some of his most intense and personal, and found him his initial success as an artist. Disinterested in flattering his sitters and able to rely upon his family’s wealth, Degas did not require, nor indeed allow, commissioned works from strangers. Instead, he would use close friends and family as his models and set to work, delving into their individual characters through his use of line, palette and composition.

The second of Auguste and Célestine de Gas' five children, Achille struggled to achieve the same success as his older brother Edgar. Described in the archives of the Service Historique de la Marine as a ‘turbulent, often impulsive boy and a consistently average student’, the young Achille’s first notable moment came in 1858 when he was placed under arrest for ‘unruliness and insubordination’, unfortunately not his final altercation with the law. Aside from the present work, the only other known portrait of Achille by Degas was painted shortly after he entered the Naval Academy and shortly before this arrest. Achille de Gas as Midshipman is currently housed in the National Gallery of Art, Washington, and offers us a wonderful insight into not only Achille’s character, but also Degas' ability to capture the essence of his sitters through his personal connection with his subjects and talent as a draughtsman. Degas shows him nonchalantly propped against a chair, his left shoulder slouched to the right and his gaze cast towards the viewer. In his visage we can see the indifference of a haughty teenager.

Disinterested by the uneventful life he was leading, Achille resigned from the Navy in November 1864, the year the present work was created, and along with his youngest sibling René, he moved to New Orleans, the home of his Creole mother. In 1872, after René returned briefly to Paris, Edgar Degas travelled with him to New Orleans, where he spent five months. Letters back to France reveal the closeness of family links and a warm, affectionate side of Degas' character. He was intensely loyal to his family, a trait that was tested when he learned of the business debts his brothers had accrued. He was forced to make huge sacrifices to settle them, including selling much of his beloved art collection. Sadly, this was in fact one of a number of catalytic moments from the 1870s that led to Degas breaking from his brother Achille, who again disgraced the family name during the Bourse Scandal in 1875 when he fired his revolver at the disgruntled Victor-Georges Legrand, whose wife had been a previous mistress. Degas' familial loyalty was evidenced again upon his death whereupon he left his estate to his only surviving sibling René and the four children of his sister, Marguerite, whom the artist had greatly adored. The oldest of these four children was Jeanne Fevre, the first owner of the present work.

Like many artists of recent centuries, Degas admired and rigorously studied the Old Masters in the early stages of his development as an artist. After leaving school he registered as a copyist in the Louvre where he would appreciate and sketch works from those great artists before him. It was likely here that he began his obsession with line and draughtsmanship that was further built upon thanks to his meeting with the great portraitist and draughtsman Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres shortly afterwards in 1855; the same year he was accepted into the École des Beaux-Arts. Degas became captivated by Ingres and Delacroix who were great rivals and subsequently was greatly influenced by both, whilst also crafting a distinct style of his own. He echoed Ingres' use of line in his painting but admired Delacroix’s use of colour. The competition between Ingres and Delacroix was in fact one which would later be echoed in the relationship between Degas and Edouard Manet, as Patrick Bade explores in his book Degas:

‘This is not to say that Manet was not capable of powerfully expressive contour, nor Degas of exquisite colour, but the chief beauty of Manet’s art lies perhaps in his sensuous use of paint, whereas Degas thought essentially in terms of line and often seems to draw with the brush. Degas disliked the glutinous properties of oil as a medium; he rarely used an impasto, preferring a matt and even surface’ (P. Bade, Degas, London, 1992, p. 15).

Another highly influential experience for Degas, and European art in the 1850s, was that of the opening of trade with Japan. The Impressionist school – although Degas thought himself separate to the movement – devoured the introduction of Japanese arts and crafts and we can see the great influence it had on artworks at the time. Unlike his contemporaries, Degas was influenced by the qualities of these prints rather than the subject matter; he noted the pictorial formats, the tight cropping and aerial perspectives, filtering it into his own style and method. These early influences in Degas' career truly allowed the young artist to flourish in a number of media and we know from study of his wider oeuvre that there was little he did not experiment with and ultimately master.

Although simple in its format, the present work is a true example of Degas' ability as a draughtsman with the brush. We can clearly see evidence of the influence of earlier studies of Old Masters from his time in Italy and as copyist in the Louvre, the rich dark brown surrounding Achille’s head greatly resembling one of Rembrandt’s piercing self-portraits. Similar too is the brushwork of the portrait, through which we can see Degas mapping out the head of his brother, the movement of strokes like that of cross-hatching, slowly building the features and highlights of the sitter’s face. As Bade comments, ‘Degas succeeds in conveying a mood of alienation and loneliness through visual means and without resorting to the story-telling devices of contemporary English painters. He uses drab, dirty, earth colours far from the joyous palette of the Impressionists’ (P. Bade, ibid, p. 27). Aside from the chosen palette for his portrait of Achille, the viewpoint differs greatly from that of his earlier portrait, Achille de Gas as Midshipman. Gone is the surly stare of the self-assured teenager, replaced instead by a distant gaze, far more contemplative, perhaps due to the recent realisation of an unfulfilling existence. The work differs greatly to many of his other portraits, as it concentrates on purely the face and not the surrounding objects, resembling more closely Degas' early self-portraiture. Notable too is the tight cropping of the head in the present work, with its posture somewhat cocked. Similarly formatted images can be found in Japanese works of the time and we therefore could be seeing the qualities of Japonisme to which Degas was sympathetic, although far more subtly employed than in other works from the period.

Portrait d’Achille Degas is a truly important work not only as the only other known portrait of the artist’s brother but also in witnessing Degas' artistic development through a particularly pivotal period in his oeuvre. The present work encompasses the unique style of the developing artist through his reverence for the Old Masters, his interest as one of the first collectors of Japanese art and his modern application of paint.

‘Without doubt the greatest artist of the period’ - Camille Pissarro referring to Degas in a letter to his son, Lucien, 1883.