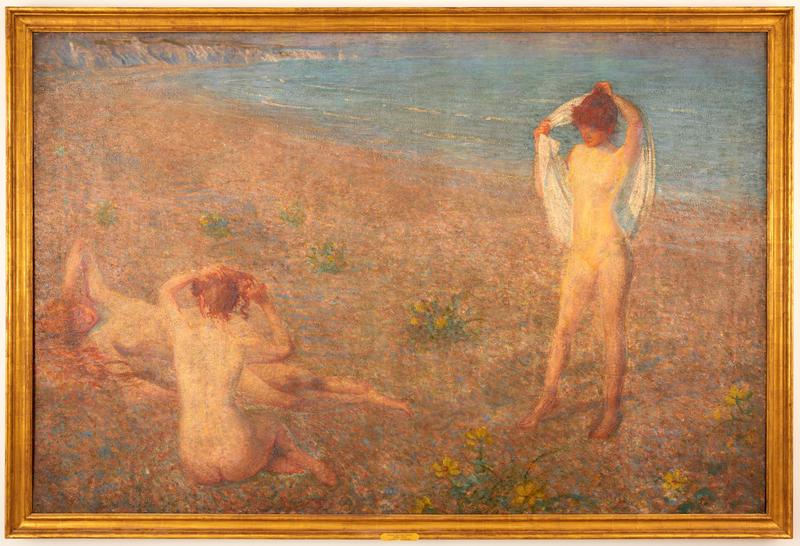

A Summer's Evening

Exhibition

London, N.E.A.C., April-May 1888, no.78Brussels, Les XX, 1889, no. Steer I (as Soir d’Eté)

Munich, Galaspalast, 1889

London, Royal Academy, Post-Impressionism, November – March 1980, no. 345

London, Browse & Darby, Philip Wilson Steer, 1985, no.3

London, Tate, Exposed: The Victorian Nude, 2000-01, no.182

Literature

‘The Pictures of 1888 – New English Art Club’, Pall Mall Gazette ‘Extra’, 1888, p. 83 (illus)‘Art Exhibitions’, The Times, 9 April 1888, p. 4)

‘Notes on Current Topics’, Yorkshire Post, 9 April 1888, p. 4)

‘New English Art Club’, The Morning Post, 11 April 1888, p. 7)

‘New English Art Club’, Pall Mall Gazette, 11 April 1888, p. 5)

‘New English Art Club’, The Building News, 13 April 1888, p. 522)

‘London Correspondence’, Newcastle Courant, 13 April 1888, p. 2)

‘The New English Art Club’, The Saturday Review, 14 April 1888, p. 443)

‘New English Art Club’, John Bull, 14 April 1888, p. 288)

‘New English Art Club’, The Graphic, 14 April 1888, p. 394)

‘New English Art Club’, Evening Standard, 16 April 188, p. 3 ‘Some Spring Exhibitions’, St James’s Gazette, 18 April 1888, p. 5)

‘London Art Notes’, Manchester Courier, 17 April 1888 p. 8)

‘New English Art Club’, Daily Telegraph, 19 April 1888)

‘Our Ladies’ Column’, Bromley Journal and West Kent Herald, 20 April 1888, p. 3 – syndicated to West London Observer, Gravesend Journal, Hawick Express, Moray and Nairn Express, Western Times and other sources.)

‘New English Art Club’, Illustrated London News, 21 April 1888, p. 425)

‘Exhibition at the New English Art Club’, The Queen, 21 April 1888, p. 491)

‘Letter to the Ladies’, Dundee Evening Telegraph, 21 April 1888, p. 2)

‘Ladies Column’, Wrexham Advertiser, 21 April 1888, p. 2)

‘Current Topics’, Essex Herald, 24 April 1888, p. 5)

‘Art Exhibitions’, Truth, 3 May 1888, p. 20)

‘Art Notes’, The Magazine of Art, 1888, ‘Art Notes’, p. xxx)

‘Le Salon des Vingt’, Indépendance Belge, 4 Février 1889, p. 3)

‘Le Salon des Vingt’, Le Courrier de l’Escaut, 12 Février 1889, p. 3)

L’Eventail, 2 Février 1889; as quoted in Laughton 1967 (below) )

Hugh Blaker, ‘Mr Wilson Steer’, The Art Journal, 1906, p. 236)

D.S.MacColl, Life, Work & Setting of Philip Wilson Steer, 1945 (Faber & Faber, London), p.190)

Bruce Laughton, ‘The British and American Contribution to Les XX, 1884-9’, Apollo, November 1967, p.374)

Bruce Laughton, ‘Steer & French Painting’, Apollo, March 1970, p.212, (illus in colour, pl.vi) )

Bruce Laughton, Philip Wilson Steer 1860-1942, 1971 (Clarendon Press, Oxford), pp.14-17, 40, (cat.no.36, illus in colour, pl.25) )

John House, Introd, Impressionism, 1974, no.132 (exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts, London) )

Alan Bowness, Introd., Post-Impressionism, 1980, no. 345, (exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy, London, entry by Anna Gruetzner, illus) )

Jane Munro, ‘Introduction’, in, Philip Wilson Steer 1860-1942: Paintings and Watercolours, 1986 (exhibition catalogue, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge) p.13, (illus) )

Kenneth McConkey, British Impressionism, 1989 (Phaidon, Oxford), pp.81,84,85,89,97 & 153, (illus in colour pl.78, p.82) )

Kenneth McConkey, Impressionism in Britain, 1995 (Yale University Press & Barbican Art Gallery, London), pp.46-47)

Ysanne Holt, British Artists & the Modernist Landscape, 2003, (Ashgate Publishing, Aldershot), p. 32)

Kenneth McConkey, The New English, A History of the New English Art Club, 2006 (Royal Academy Publications), p. 48 (illus) )

Anna Gruetzner Robins, A Fragile Modernism, Whistler and his Impressionist Followers, 2007 (Yale University Press), pp. 115, 116 (illus) )

Cicely Robinson ed., Henry Scott Tuke, 2022, (Yale University Press), pp. 77-8 (illus) )

What a blaze of sunshine! Three women bask in the bright sun… Parallels cannot fail to be established between the Baigneuses of Steer and the Poseuses of Seurat…’

Then Steer invited me to go to his house – I went there this morning. He divides the tones in our way and is very intelligent, he is an artist after all!

In 1891 Philip Wilson Steer read a brief paper on the genealogy of Impressionism at an Art Workers’ Guild soirée. In short order he attempted to contradict the belief that the movement was ‘a passing craze’ and quell misunderstandings that the Impressionists’ had apparently broken with tradition. All art, he argued, ‘is the expression of an impression seen through a personality’ and ‘his own time’ inspired the young painter as much as their own time had done for the greatest masters of the past.

Steer was no public speaker. He kept silent on years of very rough treatment at the hands of critics, did not digress into a lecture on colour theory, much less lapse into the public outrage that had cast him as one of ringleaders of the Royal Academy reform movement back in 1887 when he was painting A Summer’s Evening, the most radical work of art produced in Britain for a generation to come.

The Art Workers’ Guild paper was enough to elicit the support of one important member of his audience that evening. The twenty-eight-year-old Lucien Pissarro, son of the great Impressionist, Camille Pissarro, introduced himself and received an invitation to Steer’s studio the following day. Reporting to his father, his enthusiasm was significant – ‘Steer m’a invité à aller chez lui – J’y suis allé ce matin’, he wrote, adding with great prescience, ‘Il devise le ton à notre façon et est très intelligent, c’est un artiste enfin!’ Where others were mere dabblers and dilettantes, Steer was ‘an artist after all’.

It seems inevitable that, on that important day in early May 1891, in the studio at Maclise Mansion, Addison Road, Chelsea, Pissarro-fils would have seen the great canvas that had returned from its showing in Brussels two years earlier. This was the painting that in one leap, had lifted Steer onto the top table of the European avant-garde, and in his ‘intelligent’ application of current Impressionist techniques, demonstrated a more profound understanding of the future development of western art than any of his immediate contemporaries. Arguably, its place in the history of Impressionism has never been fully acknowledged, nor has its genesis been fully explored.

We know that when he returned from Paris back in the summer of 1884 the young painter was in a quandary. The recent Manet Memorial Exhibition had blown ‘the bottom out of the young Steer’s academic universe’, as James Laver graphically put it. Although ensconced at Walberswick on the Suffolk coast, those he admired while in France were of his generation - the likes of Alexander Harrison and William Stott of Oldham, who practiced the contemporary Naturalism of Edouard Manet and Jules Bastien-Lepage, and dismissed history painting in favour of modernité. Both Harrison and Stott had recently been working on beach scenes with which Steer’s Tired Out makes obvious connections.

Steer’s canvas inaugurates one of the most fertile periods of experimentation of any British painter of his generation. It was not motivated by the desire to discover a successful formula – commercial or otherwise – so much as by an open and unconditional quest for visual understanding. Where others would move forward with linear logic honing their skills, Steer would be capable of following several lines of visual inquiry at once – to the point where, for Bruce Laughton, writing in the 1960s, many problems of sequencing remained unresolved. To these are added a phlegmatic character that became legendary. There are no illuminating letters nor colourful diaries, and even his memories of where he had been, and when, are open to question. We rely upon the identification of exhibited works and a clear map of the wider art politics in which they emerged.

Within weeks of the sale of Tired Out, Steer was being drawn into the orbit of the nascent New English Art Club – the modest beginnings of a protest movement that sought to confront an entrenched and protectionist Royal Academy. When it opened in April 1886, it was the only artist-led exhibiting society where avant-garde practices would be tolerated and Steer would come to regard it as his principal outlet for the rest of his life. French training had made most of its founding members aware of the degree to which groups like the celebrated société anonyme – the Impressionists – had formed and re-formed in recent years in Paris, and spawned secessionist societies in other European cities, such as Les Vingt (Les XX) in Brussels where A Summer’s Evening would eventually be shown. Throughout his vicissitudes in the next ten years, Steer would be dans le mouvement.

With the artist’s work we are already in uncharted territory by the end of 1885. Exactly a year after Tired Out was exhibited in Manchester, Steer showed the impressive Chatterboxes in the Liverpool Autumn Exhibition in 1886, before its unveiling at the second New English exhibition in the following spring.

This fascinating painting informs us that the artist had been working, in the words of one perceptive critic, in a ‘French garden… in the eccentric manner just now affected by some of the “Independent Artists” in the Champs Elysées’. These ‘Independent Artists’ were specifically those who showed at the Pavillon de la Ville de Paris in the summer of 1886 - later to be dubbed néo-impressionistes by the critic, Felix Fénéon. Young painters now preferred to assert their ‘independence’ from their increasingly successful middle-aged Impressionist confrères by practicing ‘Divisionism’, an advanced form of Impressionism in which tiny touches of pure colour blend in the eye of the viewer (mélange optique). Facing his chattering children bathed in sunlight, Steer co-opts the full range of ‘new’ impressionist taches, indicating his awareness of the emergence of more ‘scientific’ approaches to the use of pure colour, exemplified in Georges Seurat’s early work. This was not, of course, a passing acquaintance. Steer is known to have taken an active interest in colour theory, owning a copy of Michel Eugène Chevreul’s celebrated Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colours (1854). In Chatterboxes and elsewhere, he had begun to experiment, believing that light would emanate from tiny touches of pigment in ‘simultaneous contrast’ – as in the work of his néo-Impressionist contemporaries in France. Thus, we discover on the reverse of an early Walberswick panel, an unfinished exercise in the method.

Like Camille Pissarro, Steer, in so far as he was aware of it, would have found Seurat’s rather mechanical pointillisme intriguing but unconducive, and throughout the following year, while pursuing different goals in works like The Bridge (Tate), he began to conceive A Summer’s Evening, the major work that, while it referred to all he had learned, would be unlike anything that he had produced up to this point. He remained committed to the general subject matter of girls resting en plein air, but for this large studio-piece, more dedicated deliberation was required, using three nude figures.

Why naked figures? In a sense the problem had been set for him by the recent Naturalist offerings of Harrison and Stott of Oldham, that must be surpassed.

His task would be to co-opt their subject matter, recognising that the female nude presented a specific problem. Naked boy-bathers in Stott and Henry Scott Tuke, had fewer taboos for a New English Art Club painter, simply because the female nude, pace Harrison, carried unavoidable classical and old master associations. When painting their female nudes in 1887 both Stott and John Lavery were obliged to resort to classical titles. Would he then be obliged to picture his models as the Graces, or the Sirens from the Odyssey, or should they be Athena, Aphrodite and Hera awaiting the judgement of Paris? Would he resort to Raphael or Titian, or even Canova, for poses? Such ideas, it seems, never occurred to him, or if they did were peremptorily rejected. The issue was raised in a conversation on ‘the Gospel of Impressionism’ between two close New English Art Club associates, Walter Sickert and Francis Bate in 1890, when the possibility of working from the female nude in the open air arose. Although not mentioned specifically, Harrison’s canvas, painted in France, and shown at the club’s second exhibition, must have begun to seem unnatural and un-English within the intervening three years. Nudity ‘would’, Bate remarked, ‘be dragging in an unnatural element in our grey English life’. Only Degas, according to Bate was able to treat women ‘exactly as they are, bathing and dressing, and not mere classicised models.’ But challenging ‘our grey English life’ was precisely what Steer set out to do, whether or not he realized its full import. His painting was ‘conceptual’, and the failure of his friends to find appropriate language with which to address its visual challenge is significant in itself. He was not so much carrying report of things seen, as making a valiant attempt to marshal all advanced contemporary empirical and craft know-how on behalf of a grand idea, released from all literary sources. His nudes were emphatically ‘bathers’, for whom no modern concealment, neither bathing machines nor book learning, were required.

Over the winter of 1887-8 the most intensely wrought of Steer’s paintings to date emerged as ‘an amalgam’, as Laughton described it, ‘of Impressionist techniques with a set-piece subject’. Having it before him constantly in the studio meant that it achieved a level of concentration impossible amidst the contingencies of painting en plein air. Brushstrokes, particularly in the foreground are broken over one another to convey the textures of sand and flesh – the latter, particularly in the standing figure, forming luminous pools of colour. Here, a sunburnt face set against a vivid cerulean tidal sweep, contrasts with the creamy surface of the model’s naked torso. Degas once remarked that painting was the art of surrounding a piece of Indian red by such a colour as to make it appear vermillion – a maxim that Steer intuitively grasped. Scale alone suggests that A Summer’s Evening was a machin de Salon to vie with the work of Seurat, an artist whose current painting he can scarcely have known. We think of Cezanne latterly wishing to make something permanent ‘like the art of the museums’ out of Impressionism, but in essence this ambition had been emerging in Paris from the early-1880s onwards. Even though the avant-garde lacked a consensus, Steer sensed its forward trajectory, and his subject, grandes baigneuses, was much in evidence in Paris as well as London. In every likelihood, visiting French capital in May 1887, he would have found that Renoir’s recent retreat to classicism was puzzling, just as Camille Pissarro had done.

But in the end, such confusing antecedents would be dismissed when the English artist confronted his large poésie in the Addison Road studio in Chelsea. His arcadia would reach further back and further forward, linking the world of Boucher and Fragonard with that of Courbet and Manet, but it was much more about facture than all of these. Indeed, like Raphael and Titian, they were a distraction. Attempting to describe this phase of Steer’s work, MacColl, who became his friend in 1890, hit upon the phrase ‘broken handling’ as distinct from ‘broken colour, which is not ‘divisionism’ either’.

Steer settled the discussion by modification from harsher to more fluent or fatter pastes, and even experimented with Old Masterish glazes over monochrome.

Such explorations won him few friends. One however, was the French expatriate painter, Theodore Roussel, who, when he came to Addison Road to draw the painting for reproduction, was currently making vain attempts to rise to the poetic sentiment in Steer’s handling while sticking to his own rigid rules. Their association and their shared use of the Pettigrew sisters as models in 1887 has not been explicitly explored. Hetty, the eldest of the three was posing for Roussel’s Bathers in 1887, when Rose, the youngest, aged fifteen, started working for Steer.

But while The Bathers was a retrenchment for Roussel, Steer, not overloaded with habit, was already breaking new ground before embarking on his greatest challenge. Where Roussel, with nods to Whistler, looked back to Jean-Jacques Henner and Puvis de Chavannes, Steer, looked forward, though of course he cannot have known it, to Henri Matisse. A Summer’s Evening nevertheless brought the two painters into the same room, and even if the Englishman might have found some of his French counterpart’s studio practice, bizarre, he would at least have been sympathetic to the ‘prismatic’ Whistler followers, among whom Roussel was revered. For a time, the members of this group, as Mortimer Menpes recalled, had ‘painted in spots and dots … [and] stripes and bands.’ However, it is only in Steer’s work that real evidence of such experimentation can be found and meaningfully deployed in the year when the Pettigrew sisters gathered with his friends for studio tea-parties at Maclise Mansion. Such civilized rituals were performed within the golden Arcadian penumbra of the summer by the sea, complete with its jeunes filles en fleurs.

In April 1888 the great canvas went on display at the third New English Art Club exhibition. Larger than the previous two shows, it was now providing a refuge for Sickert who sought to wrest control of its selection committees now that Whistler, his revered master, had been ousted from the presidency of the Society of British Artists. Steer who, unlike Sickert, had been with the New English from its inception, had less to fear from this politicking than from critics who were universally hostile to the very idea of an ‘Impressionist’ - whatever that might mean - and the unveiling of A Summer’s Evening, the pinnacle of his creative processes up to that point, was more shocking than the response to Sickert’s ‘music hall’ canvases. Immediately, the casual browsers of provincial newspapers from the Moray Firth or to Gravesend were told that a controversial painting had gone on display - something the majority would never see, nor were they recommended to see. Art, after all, was at the periphery of middle-class consciousness, when in recent months there were more important things to take in. The Socialist and Parnellite protesters had been brutally suppressed in Trafalgar Square and reports of the latest Whitechapel prostitute murder were on the front pages. ‘Penelope’, who penned the widely syndicated London letter referring to the painting, was not shy in castigating its ‘utter unnaturalness and audacity’ that made her feel ‘quite uncomfortable’ - to the point where she vowed never again to visit an exhibition containing works of the ‘Impressionist School’.

This gentlewoman was not alone in her condemnation. Others reduced the picture to its component colours and invoked Claude Monet as its inspiration, now claiming the latter as a ‘careful worker’, while his English counterpart seemed to believe that ‘squeezing a tube of colour on to a canvas’ was enough to produce a work of art. Even those who struggled to be supportive, such as The Morning Post, regarded the picture as the ‘most challenging in the gallery’, painted ‘chiefly in red, blue and yellows’ that ‘could only be seen properly at the end of the gallery’. Only The Magazine of Art, having observed the ‘almost overwhelming adverse criticism’ of Chatterboxes in the previous year, offered a qualified defence, for although Steer’s efforts to do justice to sunlight had ‘missed the mark’, he had a ‘distinct purpose’ that he ‘pursues with so much pluck that he deserves success’.

For Steer, there was no going back, even though he realized that the tides were against him. ‘They said I was wild’, he later remarked to an interviewer; and there were smaller works to supply for Sickert’s immanent ‘London Impressionists’ exhibition in 1889. The painting’s notoriety may not have guaranteed favourable reviews, but at some point after the New English opening, the artist was invited to send it to Brussels for the next Les Vingt (Les XX) exhibition – confirming of its leadership role in the larger European context. Uncertainty surrounds how this came about, but it may have been at the suggestion of one of the Belgian group’s founders, Alfred William Finch. Finch, like Steer and others, having shown with the Society of British Artists, under Whistler’s short-lived presidency, was a recent convert to Neo-Impressionism. He had seen Seurat’s Un Dimanche à la Grande Jatte, in Paris in 1886, one of the years he was also in London as a scout for the forthcoming exhibition in Brussels. Like Steer, Finch must also have observed Camille Pissarro’s conversion to Divisionism, and while he applied the method with greater consistency than his London counterpart, it must have been clear that both were on a similar path, so that when it appeared in Brussels in February 1889, A Summer’s Evening headed enthusiastic reviews, and led to discussions on Seurat’s Les Poseuses and works that Paul Gauguin had sent from Arles.

Steer cannot, of course, have been aware in advance of the obvious points of comparison between A Summer’s Evening and Les Poseuses – the front, side and back view poses - but when they were hung together it was clear that his softer, more complex and varied brushwork was favoured by Belgian critics. Where the French painter insisted on science, the British artist was more allusive, pointing to a tradition of lyricism and sensual delight – in short, a realm of luxe, calme et volupté, where resonances with Charles Baudelaire and Henri Matisse in the wider context suddenly seem apposite.

Were there to be a refrain to accompany A Summer’s Evening it would surely be that from the French poet’s L’Invitation aux Voyage. Were there to be a successor to the British painter’s experiment with Neo-Impressionism, it might well be Matisse’s aberration of 1904.

We are left clutching for theories about what might have been in the air in Chelsea in 1887. As Steer’s career unrolled, there would be times when A Summer’s Evening came back to haunt him. Three Girls Bathing, Thame, 1911 is one. Nevertheless, later variants would fail to achieve the éclat of the great picture now consigned to the racks in his studio.

Reviled after his death in 1942 by the acolytes of Roger Fry and Clive Bell, Steer’s A Summer’s Evening was rescued from the studio sale by the perspicacious Helen and Frederick Lessore of the Beaux Arts Gallery. They then passed the painting to their colourful client, Henry Talbot de Vere Clifton (1907-1979) of Lytham Hall, St Anne’s, who, following house moves, placed the picture on permanent loan through the Ministry of Works to the Foreign Office, Whitehall, in the 1960s. There, hanging in plain sight, it was rediscovered by a young Slade School of Fine Art student, Bruce Laughton (1928-2016), who began the modern reassessment of the painter’s work. Sold in 1971, it passed to new owners, but sadly was unavailable for the major Impressionism in Britain exhibition in 1995 where its centrality could easily have been demonstrated. It nevertheless remains the most significant work by a British Impressionist painter who was demonstrably dans le movement, at a time when most were scarcely aware of the impact it would have – a testament to insight, instinct, intuition or genius, that we have barely begun to understand.

Kenneth McConkey