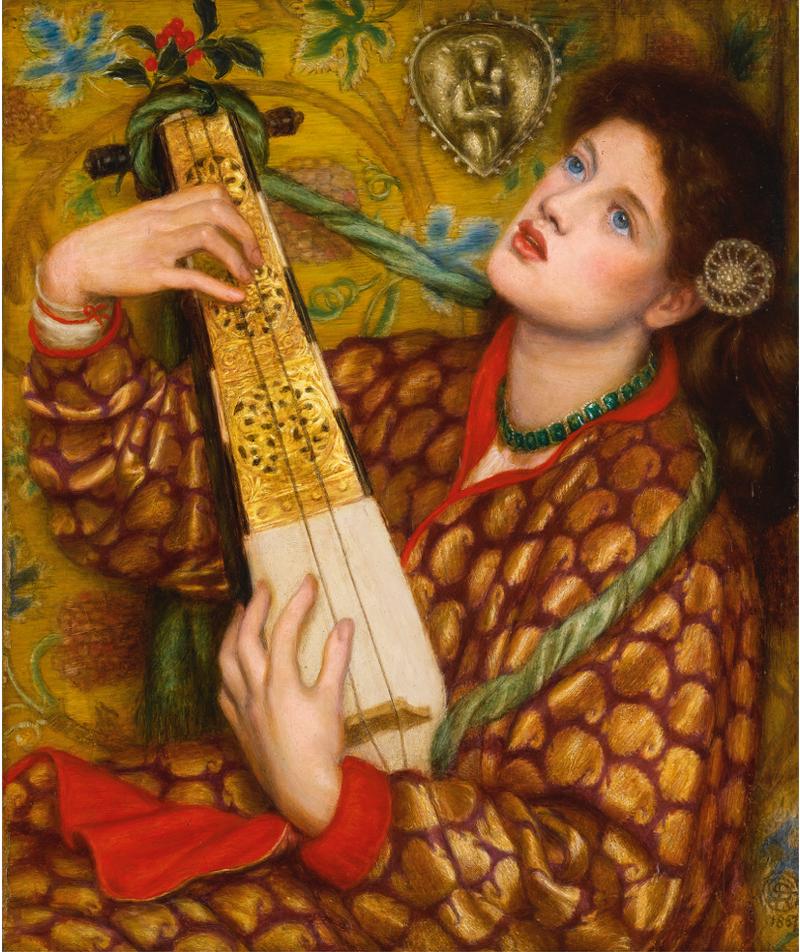

Christmas Carol

Recently Exhibited

Currently on exhibition at the Petit Palais, Paris, FranceAdditional Exhibition History

London, Burlington Fine Arts Club, Pictures, Drawings, Designs and Studies by the late Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1883, no.52 (lent by George Rae)Port Sunlight, Lady Lever Art Gallery, The Pre-Raphaelites – Their Friends and Followers – Centenary Exhibition, 1948, no.167 (lent by Viscount Leverhulme)

Newcastle upon Tyne, Laing Art Gallery, Dante Gabriel Rossetti – 1828-1882, 1971, no.65

London, Christieʼs, Treasures of the North, 2000, no.70

Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery, and Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 2003, no.109

Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery, February 2016 to March 2018

Swiss National Museum, March to July 2018.

Liverpool, Walker Art Gallery, July 2018 – February 2019

Mitsubishi Ichigokan Museum, Tokyo, Japan, Parabola of Pre-Raphaelitism – Turner, Ruskin, Rossetti, Burne-Jones and Morris, March to June 2019

Kurume City Art Museum, Japan, Parabola of Pre-Raphaelitism – Turner, Ruskin, Rossetti, Burne-Jones and Morris, June to September 2019

Abeno Harukas Art Museum, Osaka, Japan, Parabola of Pre-Raphaelitism – Turner, Ruskin, Rossetti, Burne-Jones and Morris, October to December 2019

A Christmas Carol is one of Rossetti’s earliest of a series of half-length depictions of women playing musical instruments. The connection with female beauty, music and the fashion for exotic decoration and costume were central themes of the emerging English Aesthetic movement – the revolutionary artistic style of the 1860s and 1870s that combined elements of Renaissance, Oriental and Classical styles to create an époque that was to be as important in Britain as Art Nouveau was in Europe. Central to this movement was the female musician, lost in harmonic reverie allowing herself to be observed as she creates beautiful melody, as an allegory of visual beauty as an end in itself in its most ‘red-lipped and full-throated incarnation’. Rossetti’s luscious oil paintings of beautiful women of the 1860s ‘enshrined the concept of ‘beauty for beauty’s sake’ and were antithetical to the chaste ideals and stark style of early Pre-Raphaelitism.’ (Alison Smith, Reflections, Van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelites, The National Gallery, London, 2018, p. 27).

Rossetti’s admiration for the great Renaissance Venetian colourists of the sixteenth century, such as Titian, Giorgione, Tintoretto and Palma Vecchio, who exerted a particular influence on the Aesthetic Movement, can be seen in his canvases which glow with rich, sumptuous, intense, colours. His is an original version of the Middle Ages, involving a world of the imagination, a rejection of realism or narrative in favour of mood and suggestion. This marked the second ‘Aesthetic’ phase of Pre-Raphaelitism, which ‘was characterised by a dreamier, more introspective mood, and a distance from morally improving subject matter.’ (Alison Smith, Reflections, Van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelites, The National Gallery, London, 2018, p. 27). Edward Burne-Jones perhaps summed it up when he declared, ‘I mean by a picture a beautiful romantic dream of something that never was, never will be.’

Rossetti and his contemporaries were, of course, continuing a long tradition of female figures who were depicted playing instruments both in secular and ecclesiastical art. There was a well-established motif of celestial beings playing musical instruments, often depicted as female angels, to represent heavenly music and the opening of the heavens. Admiration for the purity and simplicity of early Italian Netherlandish art of the 15th century meant that the work of Jan Van Eyck (c.1390-1441) was influential with artists of the nineteenth century and particularly the adherents of Pre-Raphaelitism. Rossetti made a pivotal journey to Belgium in 1849, the year after the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was founded, and was struck especially by the mastery of Van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece which portrayed a sense of realism significant for the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood with its ambition to study ‘Nature attentively, so as to know how to express [genuine ideas].’ Rossetti’s musician bears comparison with Van Eyck’s singers and musicians on the Altarpiece and he depicts his female subject as singing a holy song in celebration of Christ’s birth, her head upturned to Heaven and her face almost touching the silver icon of the Holy family. The painting may be seen as something of a conduit in Rossetti’s art, linking medieval influence to his ‘Venetian’ pictures of women.

The model for A Christmas Carol, Ellen Smith, was one of the lesser known of Rossetti’s ‘stunners’. She was a laundress, who Rossetti ‘discovered’ in a Chelsea street in 1863. She was a popular model in the 1860s, sitting not only to Rossetti and Boyce but Burne-Jones and others. George Boyce noted in his diary on 21 November 1865 that, ‘Nelly Smith called. She was not looking well. Has been sitting to Simeon Soloman, Poynter, Stanhope, Jones, Pinwell, and a man of the name of Linton.’ Perhaps her most famous appearance is as the bridesmaid in the left foreground of Rossetti’s The Beloved (1865-66, Tate Britain). According to Rossetti’s assistant, Henry Treffry Dunn, ‘Ellen Smith sat for several of his [Rossetti’s] sweetest pictures until the poor girl got her face sadly cut about and disfigured by a brute of a soldier and then of course she was of no more use as a model.’ (T. Hall Caine, Recollection of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1883).

Rossetti was an innovator and despised the London critics and the Royal Academy. He was, however, happy to send his paintings up to Liverpool to be seen. As Liverpool’s fortunes continued to rise and the city become a powerhouse, it rivalled the London art scene in terms of patronage. It accordingly saw the rise of wealthy patrons. Christopher Newall, co-curator of the Walker Art Gallery’s Pre-Raphaelite show: Pre-Raphaelites: Beauty in Rebellion, in 2016, describes ‘Liverpool’s centrality in the gestation of a really, critical, avant-garde art movement in Britain. The Liverpool Academy was the one place in the entire UK where Rossetti was happy to see his works exhibited.’ In 1917 the executors of George Rae’s estate sold his collection of pictures at Christie’s and it was here that A Christmas Carol, with other Rossetti paintings, was bought by the first Viscount Leverhulme, industrialist, philanthropist and politician. Most of these paintings made their way into Lady Lever Art Gallery at Port Sunlight, that he built as a memory to his wife - the greatest legacy of his philanthropy and of the energy and enthusiasms that drove him throughout his life. However, A Christmas Carol was kept in Lever’s personal possession for his private contemplation and remained within the Lever family until the 2013 Sotheby’s sale.