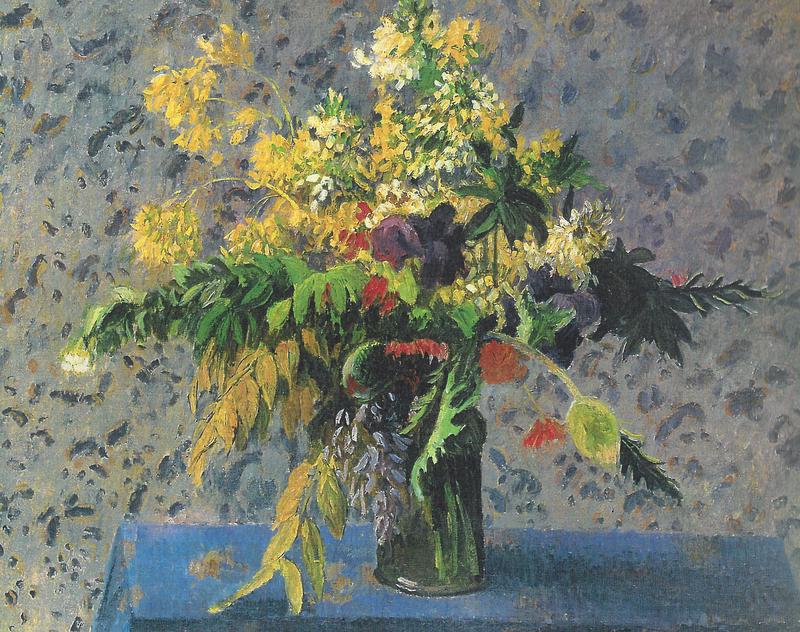

BOUQUET DE FLEURS; IRIS, COQUELICOTS ET FLEURS DE CHOUX

Exhibition

Paris, Galerie Nunès et Fiquet, Collection de Madame Vve. Pissarro, May-June 1921, no.35Paris, Galerie Charpentier, Les Fleurs et le Fruits depuis le Romanticisme, 1942-43, no.123

Paris, Galerie Charpentier, Tableaux de la Vie Silencieuse, 1946, no.52

New York, Wildenstein & Co., Magic of Flower Painting, April-May 1954, no.51

London, Marlborough Fine Art, Pissarro in England (a loan exhibition in aid of The save the Children Fund), June-July 1968, no.20 (illustrated p.50)

With Pissarro’s painting Bouquet de Fleurs; Iris, Coquelicots et Fleurs de Choux, we see an artist – a master - completely at ease in his style. There is a completeness of design and technique, with a harmony and synthesis of colour and texture; tones are perfectly balanced within a perfectly balanced structure of composition. The brushwork, although bold, has a delicacy of control and execution which gives a calm and tranquil air to the exuberance of the colourisation – the technique appears simple belying the complexity of the artist’s handling.

The importance of Camille Pissarro as an artist whose work spans the second half of the nineteenth century cannot be over-emphasised. He was pivotal in the Impressionist movement and instrumental in Neo-Impressionism. Like Degas, he studied the work of Courbet and was tutored by Corot, but unlike the temperamental Degas, he held the Impressionist group together, becoming known as the ‘dean of the impressionist painters’. He showed kindness to younger artists such as Van Gogh and Cézanne who recalled: ‘He was a father for me. A man to consult – a little like the good Lord.’ In an accolade to Pissarro after his death, Cézanne called him the first Impressionist and described himself as ‘Paul Cézanne, pupil of Pissarro.’ He wrote: ‘The brightness of his palette envelops objects in atmosphere … he paints the smell of the earth.’

Pissarro won a reputation as a landscapist and interpreted the ‘subdued radiance’ of the Japanese prints with which he was familiar into his own work, writing, ‘Paint generously and unhesitatingly, for it is best not to lose the first impression.’ Unlike Degas, he believed that painting en plein air gave the truest depiction of light and atmosphere. As his art progressed, it took on a more spontaneous look, with loosely-blended, visible and expressive brushstrokes and areas of impasto. Renoir called his work ‘revolutionary’ and the critic, Armand Silvestre called him, ‘basically the inventor of the [Impressionist] painting.’ Gauguin stated: ‘If we observe the totality of Pissarro’s work, we find there, despite fluctuations, not only an extreme artistic will, never belied, but also an essentially intuitive, purebred art … He was one of my masters and I do not deny him.’

Pissarro was born in the Danish West Indies (now the US Virgin Islands) to a Jewish father and Christian mother. He was of an anarchic disposition and throughout his life asserted his own position independent of accepted rules. He distanced himself from the values and conventions imposed by his bourgeois background and when he reached Paris, in 1855, he gradually and increasingly came to resist the aesthetic dogmas conveyed by the Académie des Beaux-Arts and by the Salons, disdaining them and refusing to exhibit at them from the 1870s. Among the Impressionists, only he and Degas persisted in their unwavering defiance of the Salons, maintaining their beliefs with an almost militant resolution. Pissarro’s headstrong courage and tenacity sustained his career, isolated as he was from his well-to-do family which placed him in an extremely precarious financial situation. He had a profound belief in the benefits of what he called ‘enthusiasm’ and ‘ardour’; a confidence that his love of work was strong enough to bolster his morale and keep him going; and an unshakable conviction that he had made the right choice (‘if I had to start all over again, I would not hesitate to follow the same path’). He was the only artist who showed his work at all of the eight Impressionist exhibitions from 1874 to 1886.

The Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, compelled Pissarro to flee his home and he arrived in London. Going against convention, he married his mother’s maid, Julie Vellay, a vineyard grower’s daughter, in Croydon with whom he went on to have seven children. Their six surviving children all became artists. When he returned to his home in France in June 1871, he discovered that of the 1500 pictures that he had painted over twenty years, all, save forty, had been destroyed by Prussian soldiers.

From his arrival in Paris in 1855 until his death in 1903, Pissarro displayed a profound and insatiable curiosity about the work of his younger colleagues. He was mentor to Cézanne, Manet, Renoir, Gauguin and Van Gogh and shared an interest in Neo-Impressionism with Signac, Maximilien Luce, and in particular, Georges Seurat. He was influenced by the work of his two eldest sons, Lucien and Georges and a few years before his death, he was providing advice and guidance to two of his sons’ friends, Henri Matisse and Francis Picabia. He managed to remain on mutually respectful terms with such difficult personalities as Degas, Cézanne and Gauguin and became known as ‘Père Pissarro’ by his fellow impressionists. Mary Cassatt referred to him as ‘the gentle Camille Pissarro’ and suggested that he was a teacher who ‘could have taught the stones to draw correctly.’