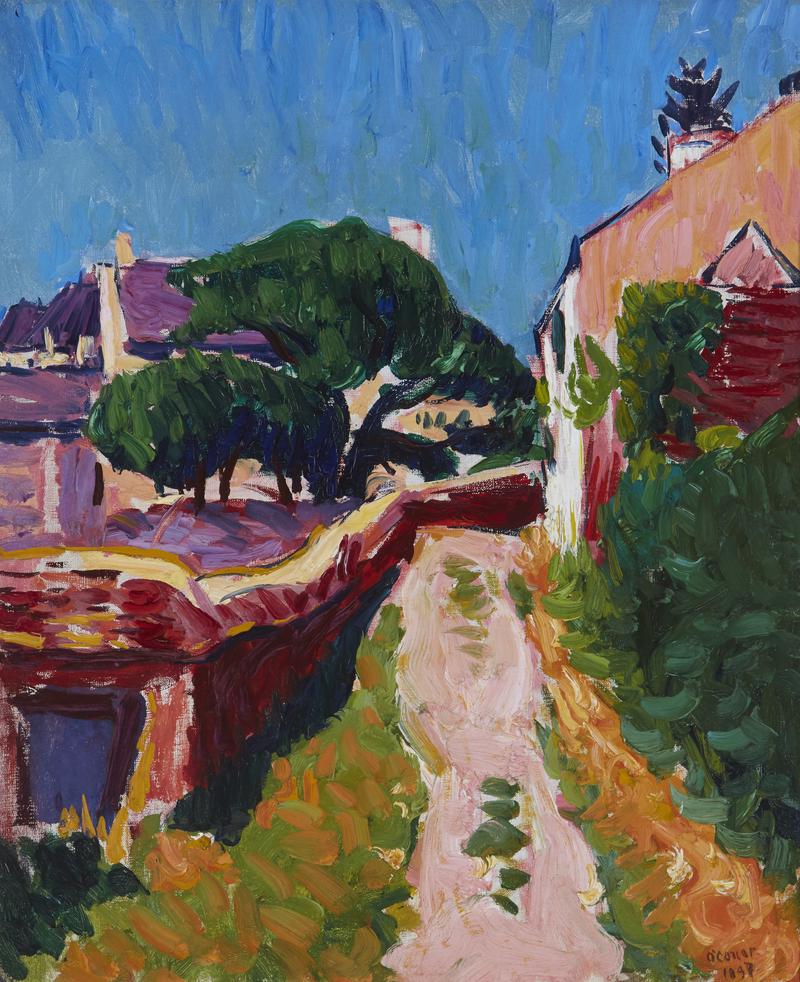

Entrance to Village, Brittany

Exhibition

London, Roland, Browse & Delbanco, Roderic O'Conor paintings; collectors' drawings, 19th and 20th century, 1957, no. 16‘I like Brittany; here I find a savage, primitive quality. When my clogs echo on this granite ground, I hear the dull, muted, powerful sound I am looking for in painting.’

Paul Gauguin

In 1895 O’Conor left the town of Pont-Aven in Finistère and moved his base further inland to the picturesque village and artists’ colony of Rochefort-en-terre in the Morbihan district of Brittany. Pont-Aven had become overrun with artists and tourists by this date, and O’Conor would have been charmed by the unspoilt character and colourful history of Rochefort with its twelfth-century church and fourteenth-century ruined castle. He put up at the local inn, the Hôtel Lecadre, where he was sufficiently removed from the civilising influence of the railway and of Brittany’s larger towns to be able to find fresh inspiration in his new surroundings. Doubtless he would also have spent time reflecting on what he had learned from the friendship he cultivated with Paul Gauguin, before the latter left France for good in June 1895. O’Conor had, in fact, been invited to accompany him to Tahiti but declined.

Dorothy Menpes, writing in 1905, summed up the evident charms of Rochefort-en-terre: ‘There is nothing modern about Roche-fort. The very air is suggestive of antiquity … Rochefort, like the Sleeping Beauty’s palace, has lain as it was and unrepaired for years. Moss has sprung up between the cobble-stones of her streets; fern and lichen grow on the broken-down walls … Rochefort is a typically Breton village. Nowhere in Switzerland does one see such ancient walls, such gnarled old apple-trees, laden and bowed down to the earth with their weight of golden red fruit … Everything in Rochefort seems to be more or less overgrown.’ (Dorothy and Mortimer Menpes, Brittany, 1905, pp. 16-19). Although Menpes goes on to note that, ‘Nearly every house in the village has something noble or beautiful in its construction’, and indeed O’Conor was accommodated in one such building (his hotel had a columned entrance and a smoking parlour), when choosing a subject he typically favoured more humble dwellings, accessed via steep narrow paths and seemingly losing the fight against nature’s relentless advance. The vivid reds, pinks, greens and blues of Entrance to Village, Brittany evoke the vibrant palette favoured by Gauguin, although the bold, expressive brushstrokes that animate the surface of O’Conor’s painting are particular to him. As Denys Sutton noted in an important article that constituted the first serious study of an artist who, at that time, was still a, ‘little-known member of the Pont-Aven circle’ (Studio, November 1960): ‘Some change in his style was, however, apparent in 1897 and in the Village Lane (the present work) datable to that year, the handling is exceedingly fluid; he favoured pinks and oranges, which colours frequently appeared in his later works. His use of direct colours, placed unbroken onto the canvas, suggests some affinities between his practice and that of the Fauves.’

To fully appreciate the radical modernism of O’Conor in the closing years of the nineteenth century, when he was staking his claim as a committed and adventurous colourist, it is instructive to compare this French landscape with one painted by a fellow countryman and contemporary. John Lavery’s The Bridge at Grès (Ulster Museum, Belfast) dating from around 1897, is essentially an elegant, tonal rendering of a picturesque scene featuring two women in a rowing boat relaxing from their labours beneath the arches of a bridge. By way of contrast, O’Conor exaggerates local colour, eliminates unnecessary detail and minimises spatial recession in his village scene.

O’Conor’s lane is bathed in brilliant sunshine. The central axis is closed off by stone walls and foliage; the windows and doors of the houses are hidden from view, the garden gate in the wall is firmly shut, and the atmosphere is sultry, as if the weather is about to break. There is no human incident in the painting and by keeping the viewer at a respectful distance, O’Conor preserves a sense of the Breton ‘other’, that perception of Brittany as a country apart with its own language, culture and folklore that so impressed Gauguin. The French artist had famously declared in 1888: ‘I like Brittany; here I find a savage, primitive quality. When my clogs echo on this granite ground, I hear the dull, muted, powerful sound I am looking for in painting.’

O’Conor spent three years in Rochefort-en-terre before moving back to Pont-Aven in 1898. They were lean years in terms of his artistic production and frustrated by bouts of ill health, but the inventive use of colour pioneered in works such as Entrance to village, Brittany would stand him in good stead when he embarked on his extensive series of Breton seascapes in 1898. The unadulterated swathes of pink and crimson, purple and orange that came to the fore in a handful of experimental village street scenes would shortly dominate the thirty or so views O’Conor painted of the wild rocky coastline.

We are grateful to Jon Benington for his kind assistance with this essay.