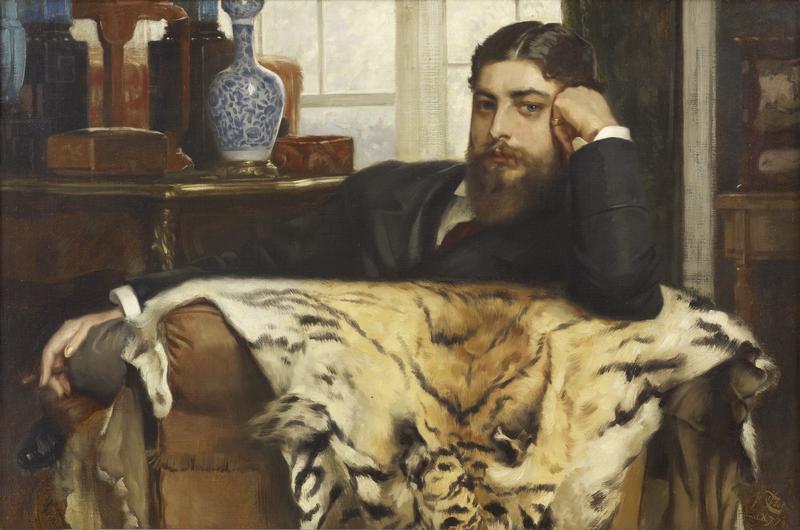

Algernon Marsden

Exhibition

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, James Tissot: Fashion & Faith– Legion of Honor , 12 October 2019 – 9 February 2020The Musée d’Orsay, Paris, James Tissot: Fashion & Faith– Legion of Honor, 2020

Ashmolean, Oxford, 2016-2019

Exhibition Archive

Tissot’s portrait of Algernon Moses Marsden captures the man at his most successful. The sitter appears a debonair and sophisticated man-about-town; he holds a cigar nonchalantly in his right hand and gazes directly at the viewer, his head leaning lightly on his left hand, a subtle gold ring shines on his little finger; he is the epitome of insouciant style, and fashionable, suave ennui. He sits on a leather chair and the space surrounding him is indicative of a man’s study or fashionable club. The blue and white Chinese vase and case placed on the table behind hints at an educated and sophisticated taste for collecting fashionable blue and white Chinese porcelain. The tiger skin Marsden leans on adds a hint of exoticism and acts as a foil to the otherwise plain leather armchair, giving a startling suggestion of Marsden’s virility and possibly his animal magnetism. Tissot used the tiger skin in his paintings several times, to add textural complexity and to illustrate the lushness of the Victorian leisured life.

Algernon Marsden (1847–1920), was Tissot’s art dealer for a short time in the mid-1870s, although there is little information on any of Tissot’s paintings that Marsden may have sold. Tissot’s painting In the Conservatory (Rivals), c. 1875, was listed at auction as having originally been ‘(probably) with Algernon Moses Marsden, London’ and it is suggested that Marsden modelled for one of the figures in this painting. In 1876, Marsden purchased Tissot’s painting, Marguerite in Church (c. 1860), from the dealer Goupil for £315.

Tissot’s portrait of Marsden remained in the Marsden family for nearly a century. The setting of the portrait is the elegant new studio of Tissot’s home in St. John’s Wood. Algernon Marsden was, in fact, a more colourful character than this urbane portrait of him suggests. He was born, one of fourteen children, to Isaac Moses and Esther Gomez. His father came from an impoverished background but established the successful firm of E. Moses & Son, ready-made clothing manufacturers and retailers, in 1832, developing several ‘emporiums’ at prime locations in the City of London. In 1846, the premises at Aldgate had grown to four times its original size, and soon nearly doubled again, becoming the largest shop in London. ‘… the emporium itself was designed to attract custom. It had a high classical portico, tall ground-floor windows, and bright interior lighting, and offered impeccable service to any who wandered in. No building was like it in all of London. Second, little expense was spared in advertising the top-quality clothes, available at such cheap prices and only in the emporium. The advertisements were sometimes placed in magazines but usually they were freely distributed throughout London in the form of little booklets. Many of the latter have survived and show that popular current events were used as the basis for a doggerel (probably composed by Isaac) on the emporium’s virtues. Third, clearly displayed fixed prices cut out any haggling and enabled staff to spend their time cultivating the image of a well-to-do West End bespoke tailors by standing in attendance on customers.' (Andrew Godley’s entry on Elias Moses, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004). The emporium housed a collection of stuffed lions, tigers and giraffes as an added attraction for customers and possibly this is used as a reference point in Tissot’s portrait of Marsden.

Isaac Moses success rose rapidly. In 1855 he bought the lease to a grand new house at 23 Kensington Palace Gardens. A year later, he commissioned the architect J. D. Hopkins to design a two-bay, three-storey extension at the south-west corner and a bow-fronted ballroom at the back. In a five-day auction of properties in St. John’s Wood in 1858, Isaac Moses, one of his sons-in-law, and his son-in-law’s father purchased a number of properties. In 1858, Isaac purchased Lord’s cricket ground for £5,910, selling it in 1866 to the Marylebone Cricket Club for £18,333. By the 1860s, E. Moses & Son had several branches in Britain and throughout the Empire. The firm’s pioneering marketing techniques as well as the import of the Singer sewing machine in the 1850s and 1860s, brought ready-made versions of styles worn by the rich at a price affordable to the working-class. In 1865 the entire family adopted the additional surname Marsden.

Algernon Moses Marsden married Louise Frances Hyam (1850–possibly 1924 or 1928). The Hyam family lived in Ipswich, Suffolk and was affiliated with Hart and Levy in Leicester, a firm founded in 1859 that became one of the largest clothing manufacturers in Britain. Rather than join the family clothing business, Algernon established himself as a picture dealer at the Conduit Street Gallery in St. James’s. When Tissot painted Marsden at the age of thirty, he appears sophisticated and well-to-do, but his high living cost his father thousands of pounds and resulted in his bankruptcy four years later in 1881. Marsden was then employed by the King Street Galleries, St. James, and had accumulated debts. In August of 1882, his bankruptcy was annulled because the debts were settled in court through a Trustee. His father died in 1884, disinheriting Algernon but providing legacies for Algernon’s wife and children. In one of ten codicils to his will, he states, ‘my said son Algernon Marsden has recently been adjudged a Bankrupt’. Algernon was again in the bankruptcy court in 1887, where he stated that when money came in, he “got rid of it” by gambling, particularly at the racetrack. He admitted to overspending for weeks at the fashionable resort of Eastbourne. He described his profession as an art dealer as a “peculiar and speculative one.” When he added that it was always a “fluke” to get hold of a man with money, he brought laughter from the court. In 1901, bankrupt for at least the third time, Algernon, at age fifty-four, fled to the United States with another woman, leaving his wife and ten children behind. He died eight years later in upstate New York.

James Tissot fled Paris in the aftermath of the Commune in late May or early June, 1871, and established himself in the competitive London art market. In 1873, he bought the lease on a house with a large garden in Grove End Road, St. John’s Wood. It is possible that Tissot made the acquaintance of the Marsden family through his interest in painting clothing or through the Marsdens’ ownership of property in St. John’s Wood – or, it may be that he merely met and liked the engaging, witty young Algernon Moses Marsden. Graham Reynolds suggests that one of the reasons Tissot was so successful was that along with his sophisticated training and immense talent, when he came to contemplate and depict the beau monde he had the advantage of being an outsider. This meant that he could take ‘his men and women at their own valuation’ and was not prejudiced by any inherent British snobbery. Newly-wealthy industrialists sought his work as they enhanced their social status by building art collections. Tissot was a ‘a grand interpreter of the high life’ (Reynolds) and his paintings showcase the splendours available to the wealthy: exotic plants from around the world, oriental and eighteenth century objets d’art, and beautiful women adorned beautifully in the latest fashions. Tissot’s paintings were bought by collectors whose lifestyle mirrored that depicted in his art.

James Tissot’s art was strongly represented at the Tate Britain exhibition, Impressionists in London (2 November 2017 – 7 May 2018). Whilst Tissot was not an Impressionist himself, he did share the light and deftness of touch that their works display. His paintings stand by themselves as technically brilliant and beautifully executed works which act as a great record of the high life, the fashion and the luxury and the immense wealth that was generated in London in the second half of the nineteenth century and describe, sometimes satirically, the manners and social mores of the day. No other artist records the opulence that these luxurious narratives display better than Tissot.